A Method To Assess The Cumulative Effects Of Land Use & Dispossession On The Indigenous Seasonal Round

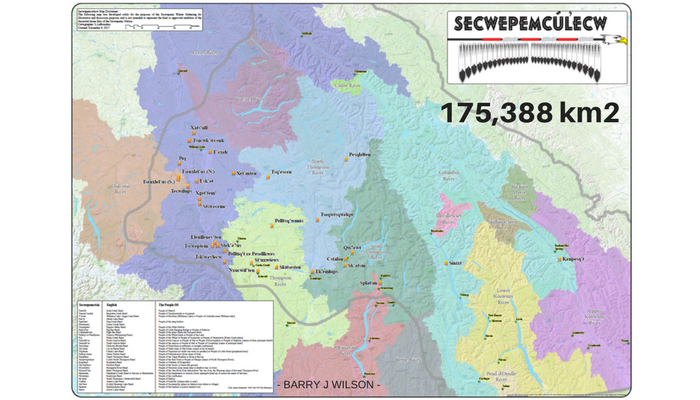

May 14, 2018I've been leading a lot of #CumulativeEffects work in Secwepemcúl’ecw, the unceded Traditional Territory of the Secwépemc Nation. The people of this indigenous Nation have lived in southern British Columbia, Canada, for over 10,000 years and their Territory is the largest of all First Nations in British Columbia occupying almost 20% of the Province.

In the Virtual Time Machine Podcast, I discuss how we can travel back in time to see how the Secwépemc lived for thousands of years, directly from the land, long before the arrival of Settlers. In the spring, summer and fall, they would travel to different areas of Secwepemcúl'ecw to gather the various resources from they land they needed to survive. This moving around for resources is characterized in English as the 'Seasonal Round'.

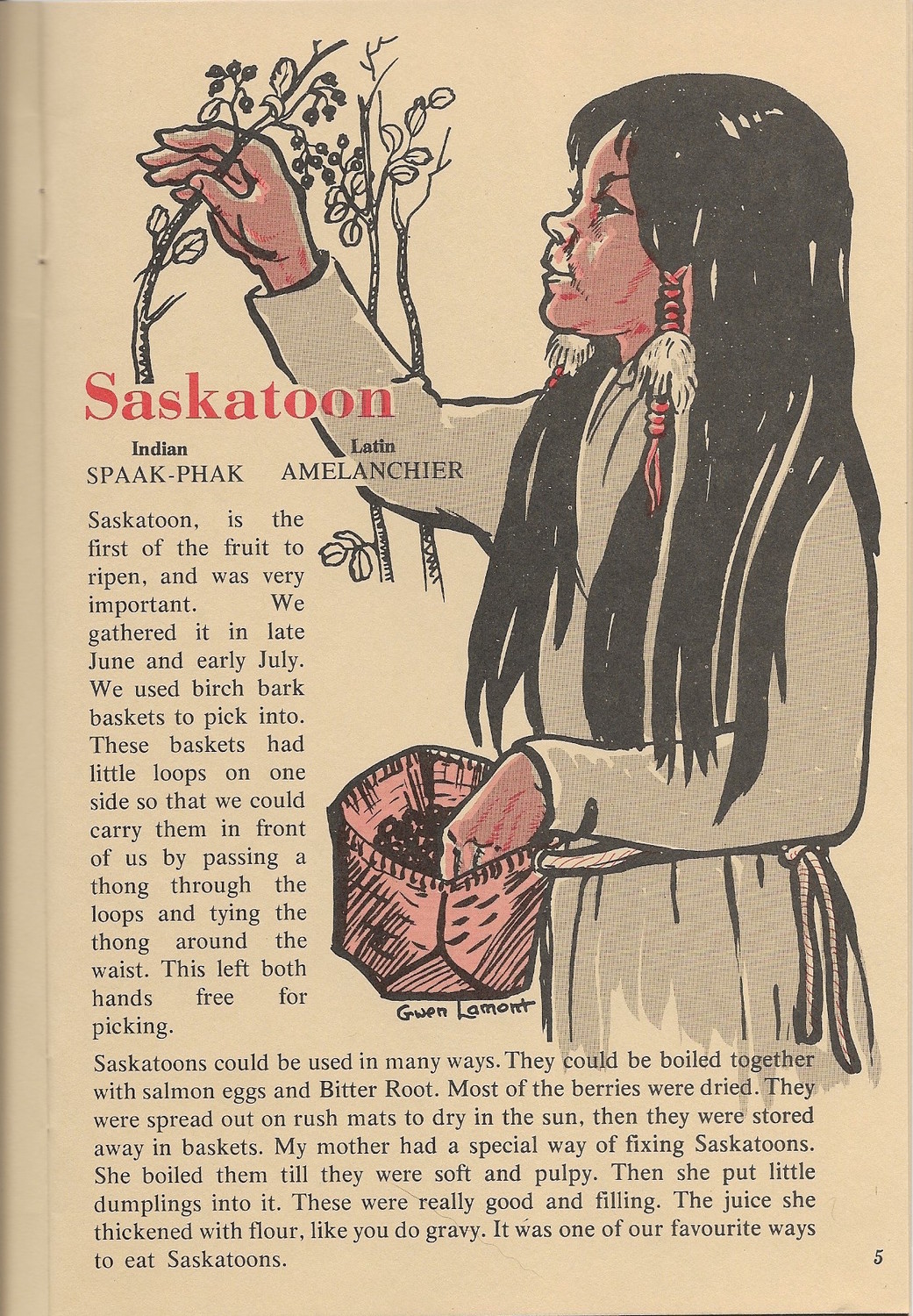

Obviously, food was a critical resource. Here is an excerpt from BC School District 73 website about this.

“In winter people moved to their winter villages and settled in the underground pit houses."(see footnotes for source)

Here’s a very cool thing. You can download an app called Secwépemc and hear the words of the language and it’s definition. Here’s the Secwépemc word for pithouse: "c7istkten."

"So, short day trips were made for ice fishing and hunting local game. Families would also rely on their winter stores of dried salmon, deer, elk, plants and berries.

In spring the Secwépemc would venture from their winter villages in pursuit of fresh food sources. After a long winter, fresh edible green shoots of fireweed, cow parsnip, balsam root and Indian celery were welcome treats. Each plant was harvested as they became available and immediately consumed or preserved for future use.

By the end of June saskatoon berries would be ready for picking. Large amounts of these berries were harvested and dried for future use. Other berries such as strawberries, thimble berries, soapberries and raspberries soon followed. Much of the summer was spent gathering a variety of berries.

Towards the end of summer, families would begin fishing for spring and sockeye salmon at different weir sites and riverbanks. The salmon would be dried and stored for winter usage.

From September to October the primary activity was hunting. The game hunted included deer, elk, caribou, bear, mountain goat, and beaver. Small animals such as grouse or ducks were mixed with berries and fat and made into dried cakes for storage. As the winter stores grew fuller, the Secwepemc would once again settle into their winter dwellings.

To this day, wild foods are a very important value for the health of the Secwépemc people. The nutrients in those plants and animals are often not available in “store bought” food and so access to these wild resources is critical for their health today, and into the future.

Clearly the key priority I’m talking about is access to the traditional round. There are two main values there that are linked – the presence of the seasonal round resources to be harvested, and then having access to them.

In recent cumulative effects assessment work I was directly involved in with Stk’emlúpsemc te Secwépemc, which is one of the seven divisions of the Nation, we quantified an estimate of the #CumulativeEffects of land use on the protein component of the seasonal round. Several persons were involved in the project in addition to myself including Sunny LeBourdais, Amanda Watson, Justin Straker, Matt Carlson, Melissa Iverson, Sean Sharpe and Ryan MacDonald.

The characters in this story that contribute to seasonal protein include ungulates, fish, birds and bears. So in order to understand changes in the availability of the protein seasonal round for the Secwépemc people, we first needed to figure out a way to measure the relative abundance of the key species. Filtered through the criteria I shared in my article "How To Select Indicators That Will Help You - And How Many Do You Need" for good indicators, we created an index of the protein sources that included mule deer, white-tailed deer, elk, moose, mountain caribou, sharp-tailed grouse, grizzly bears and the full guild of native fish. Then we were able to compare the relative value of habitat effectiveness today and in the future with pre-contact conditions and therefore quantify the changes and drivers of that change. In essence we were using a virtual time machine to look back thousands of years and compare that time with today and 50 years into the future.

You can download my excel template here: https://www.barryjwilson.com/p/ChoosingIndicatorsTemplate

In order to estimate accessibility, we created a composite index that quantified the relative change in access to harvest these resources compared with pre-contact times. We measured three major changes - the removal of access by fee simple selling of the land or water to Settlers by the BC Government, conversion of the land or water to footprint (e.g. cities) and finally the allocation of a resource to an individual or corporation through tenure and licensing. For example, non-indigenous hunting and fishing affects the total abundance and distribution of animals that are available for harvest by people. In some cases human footprint has eliminated a species – like the dams on the Columbia River have removed anadromous salmon from almost all of the BC waters of this huge watershed.

In future articles I intend to share with you how to create a habitat effectiveness index for critters like these as well as composite indeces. Follow me and those articles will come up in your feed when they are published and you'll be sure not to miss them.

Leave a message here and let us know what kind of indicators are most important to you in your assessments.

I discuss this more in the Virtual Time Machine Podcast Episode 2.2 You can also subscribe to my blog and my YouTube Channel for more excellent content!

References:

1. http://secwepemc.sd73.bc.ca/sec_village/sec_round.html

2. Berry picking illustration source: Lak-La Hai-EE, Volume 3, Written by Ursula Surtees, Illustrated by Gwen Lamont